You are the CEO of a well-known asset management company and are sitting in a meeting with a new data vendor, your new portfolio manager (PM) who is an expert in alternative data, and your compliance officer.

The Data Pitch

The data vendor has data showing exactly what each public company’s CEO and all their workers ordered for lunch every day since Jan 1st, 2011, and he shares a case study where, using the patterns in the food data, their proprietary signal successfully predicted an impending merger of company X that had been shopping for strategic partners, with conglomerate Y. The senior management of public companies X and Y started eating more steaks, fries and pizza three months before the actual successful merger. The vendor’s resident food scientist — an authority in the field, shows convincing and intriguing studies about protein, sugar, and fat correlations with dopamine receptor activity, serotonin and testosterone levels, and how changes in senior leadership’s food consumption patterns might signal important business events on the horizon. Even if the exact event remains unpredictable, buying options ahead of time that gains value when the volatility and activity in X and Y increase after the news breaks officially could be profitable.

It is all very interesting and horizon-broadening; you are reminded why finance can be fun! The vendor came to you first because you are known as a sophisticated client and these data are not accessible to many people yet — especially not in a systematic, compiled way. Your star portfolio manager is salivating. She is still asking all the hard questions ranging from data quality, data completeness, to the high likelihood of back-fitting — “What about the cases where people just changed their food habits randomly and nothing happened?”— but you know from experience that she really wants the data and can put the findings to good use by collating the data with the existing data sources your firm already has.

You also wonder how much pension fund ABC, your tough and intelligent investors, might like a cool story from this project: “Hey we really know the companies in our concentrated equities portfolio. We even know what they are eating! We found that going long protein and short empty carbs actually made 3% alpha in our concentrated event-driven strategy.” Insert a fun discussion about food, and you might just have retained a client that would have switched to smart beta.

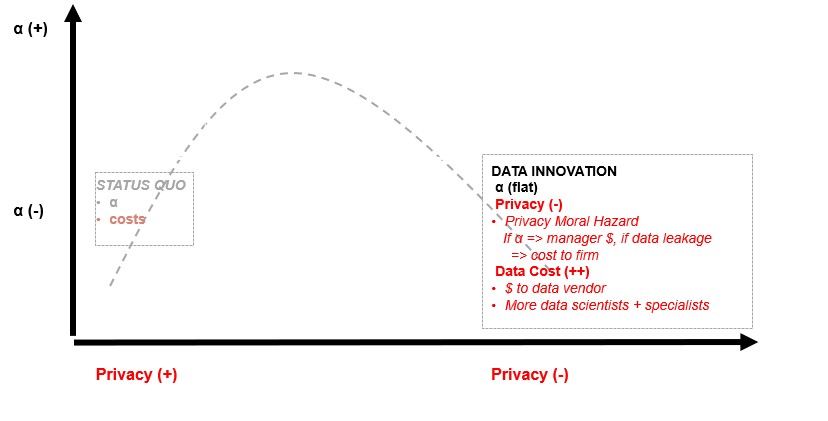

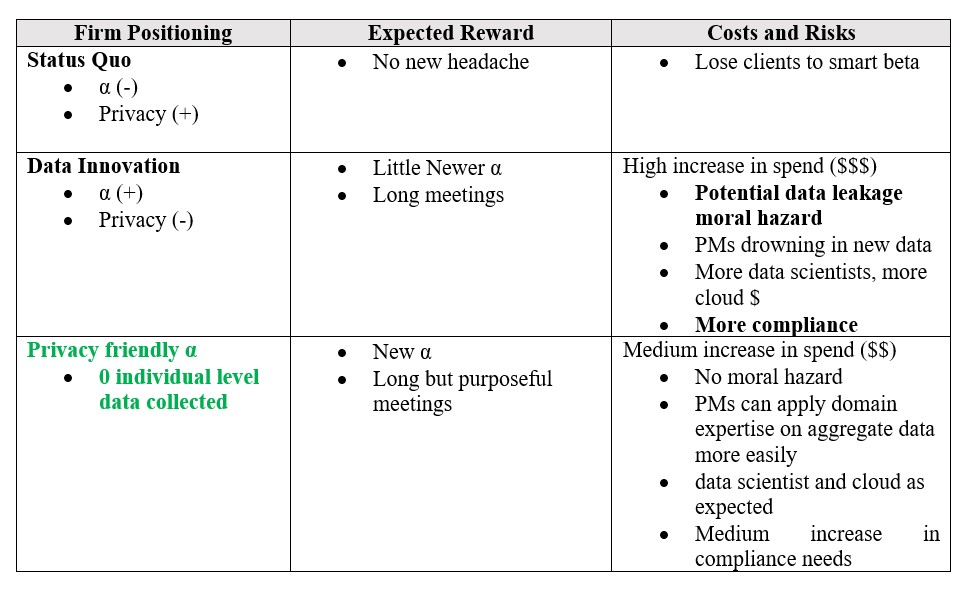

Alpha vs. Privacy

On the other hand, the data are expensive and you are concerned about privacy: I would not want people to know what I am eating.

Your compliance officer points out that, if no one else is using these data, that is actually a bad thing, and you know he would prefer you not to buy these data. Additionally, he raises the issue of informed consent. The informed consent issue seems non-trivial since most people do not really understand what they click ‘yes’ to. Cameron Kerry of the Center for Technology Innovation at the Brookings Institution recently wrote: “In a constant stream of online interactions, especially on the small screens that now account for the majority of usage, it is unrealistic to read through privacy policies. And people simply don’t.”

But this is unfamiliar terrain for the compliance officer. The data vendor had produced the consent forms which the CEO and his colleagues had ticked off on their iPad menus when ordering their food; these forms did contain explicit consent information in English and Spanish explaining that the data about their consumption patterns could be shared with third-party vendors. This conforms with state and federal laws on informed consent, and the diners are adults and highly educated English speakers. Further, what the data vendor was offering was not personal health information but rather data about the CEO and his team’s eating patterns, not the more intimate data found in medical records. Finally, and most importantly, the data vendor was using these data to speculate on a theory. He was in possession of no independent, material market-moving information not otherwise known to the general public about company X’s potential significant transactions in the imminent or distant future. Although one of the diners (the CEO) is an insider, “material non-public information” refers to clear information about a company that could affect its share price and investment decisions as soon as the information was made public. Imagine if the lunch conversation was put on video on YouTube™, the compliance officer considers. Would this then be “material information” that could move the stock price? No. So he signs off. He does, however, speculate on a different scenario: suppose the CEO had been caught drinking several bottles of wine at lunch with his colleagues on a workday. Might that scenario have cast a shadow on management’s perceived competence and thereby constitute materiality? He parked this scenario away in his head since it did not happen here.

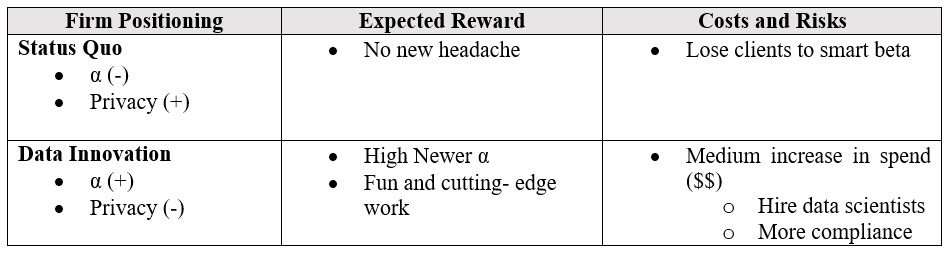

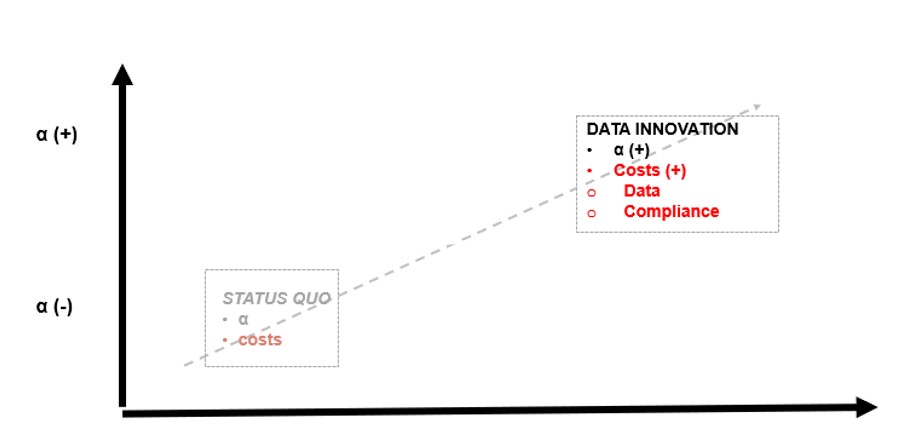

Here, the positions of the vendor, PM and the compliance chief are not unexpected and you know ultimately you will try to mediate and, together with your team and try to reach a reasonable decision. The question facing you is: “Are the costs and risks of these data worth the expected reward?”

Your PM replies: “Very simple!” To earn higher returns, we must take more risk and pay more. And sure, the privacy of a few people may diminish in a theoretical scenario with these types of consumption data, but senior management had signed up for a certain amount of risk when they took on public roles in a public company. Wouldn’t the slight potential diminution of privacy of a few people justify more dollars in the hands of retirees?

But is that true?

More costs arise

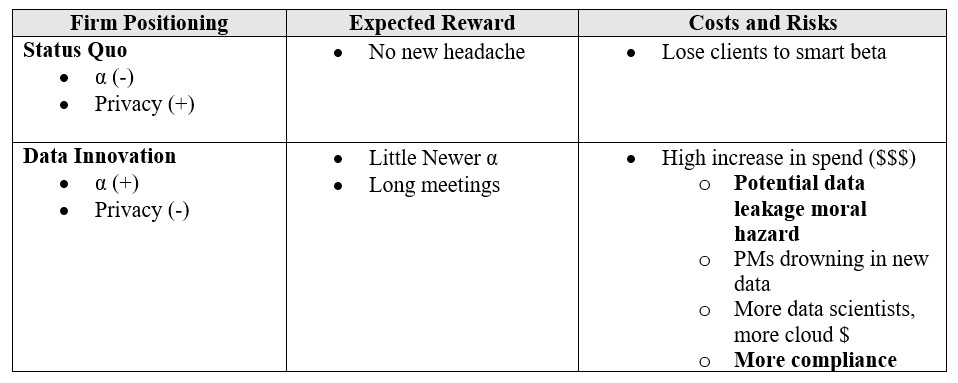

Over time, you realize that there are some unexpected costs: after obtaining these new data, you had to hire various specialists as consultants to process the data and then everyone had to understand what these specialists were really saying. The meetings become tortuous since the PM seemed like the only one who had a clue about the biology and brain chemistry even though the head quant and the main food scientist were in the room and only too willing to explain to whoever would listen.

The head quant wants more cloud storage and three more interns to continue work on her multi-dimensional map that relates food consumption patterns of senior leadership in public companies to what they say in their speeches, including the earnings calls. It is a beautiful piece of research that combines neurochemistry, graph theory, and natural language processing (NLP) to determine the effects of food on mood. However, so far, they have only worked on one sector since most of the time has been spent ‘building the engine.’ And one could drive a truck through the confidence intervals in their conclusions.

On the reward side, there does not seem to be a ton. Yes, your firm espouses patience in investing but it has been six months and your team has not found any systematic alpha signals that you honestly believe in. You have second thoughts about your data strategy and are now wondering where the sweet spot is. Is it sector-level data? Is it only doing anomaly detection rather than mapping all food everyone is eating?

It turns out that this lack of results from hyper-personalization and vast amounts of analysis is not uncommon in other fields. In their influential meta-study on the economics of privacy, Aquisiti et al. mention that while large sums of money are spent on targeted advertising — using sophisticated techniques from Web bugs, to cookies, to browser and device fingerprinting — its effectiveness is unclear. Blake et al. measured the effectiveness of paid search by running a series of large field experiments on eBay™ and found that the returns from paid search are a fraction of the conventional non-experimental estimates and are even negative in some cases! In the same paper, the authors mention other kinds of informed discrimination such as in hiring and fairer outcomes were achieved after removing information.

The moral hazard of alpha and privacy breach

What if these hyper-personal data help generate some alpha for a few years and then there is a terrible leak that exposes sensitive information about people’s DNA to malicious hackers in a different country? How does the current incentive structure play out? If the firm is organized such that the PM and the quant team could reap significant benefits from the alpha signals derived from new data, and compliance or the CEO bear the long-tail risks in case of a leak, then there is room for moral hazard. The PM and the quant teams are incentivized to be aggressive in procuring these data and exploiting them to the utmost without regard for privacy or the tail risks. And these long-tail costs can be real. Privacy is context dependent and malleable and individual humans are experts in making the trade-offs that work best for them. Ex-ante it is not clear that asset managers should become co-owners in individuals’ trade-offs of interactions ranging from finding partners to learning from online courses to navigating streets, to celebrating our newborns.

Potential cures like data anonymization do not work as well as we may expect. In a recent paper, researchers de Montjoye and Hendricx showed that 99.98 percent of Americans were correctly re-identified in any available ‘anonymized’ dataset by using just 15 characteristics, including age, gender, and marital status. Additionally, if Capital One™ — a big company known for being tech-savvy — could not protect its customers, what is the guarantee that a smaller asset management firm can? Public opinion has also been shifting against the violation of privacy with articles published in prominent media outlets such as Bloomberg on hiding from silicon-valley and the prestigious Nature journal penning an editorial on the ineffectiveness of data anonymization and the corresponding need to protect people’s privacy vastly more.

So when a ‘privacy crisis’ happens in asset management following some a broad-scale leak, public opinion of most people who do not realize how much information about them is available may swiftly and dramatically turn against asset managers who may be better off self-regulating. The pressure to deliver outperformance is never-ending and intense; this is large topic whose solution relies on understanding a wide range of ongoing social science and empirical research from different disciplines. Consequently, we not profess to have the answers but believe that other fields offer some immediate nuggets of insight:

Learning from Healthcare: The Risks of Exposing Personal Data in the Context of Urgency

So ingrained in healthcare research is the risk of data leakage that Faculties of Medicine have long had Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) pre-assess data methods and potential datasets for demonstrable downstream benefit well prior to the collection of any research using human subjects. The IRBs, consisting of arm’s length assessors, function independently. Research projects built around methods that do not collect personal data – for example, a survey of hospital protocols on IT usage – can be declared exempt from in-depth IRB protocol reviews, which is a relief for researchers because the process of a full review can be taxing and delay the research significantly. There is thus an inherent incentive to avoid the collection of personal data unless the ROI of linking datasets – the mapping of clinical outcomes data to specific surgical procedures, for instance – can lead to important discoveries such as finding out that one of many different surgical procedures is the only one that results in longer post-surgical survival. This research requires personal data but is obviously worth the potential stress and delay of going before an IRB.

Healthcare has learned from its over-estimation and hype over the value to be derived from personalized data. For example, in the search for personalized medicine, a potential route to better cures is to match genomes to drug therapies – the idea being that people with specific gene configurations would respond better than others to specific drugs. To this end, many drug trials now collect genetic data. Although there are anecdotal stories that this approach sometimes has helped, it has not produced the miraculous results people hoped for. There has been a lot of genetic data collected (which is a major privacy risk if accessed by unauthorized persons) but no one knows what to do with all those data. Healthcare has also seen the damaging effects of information overload: Researchers have analyzed the situation through the concept of “filter failure,” noting that the main problem is not that there is too much information, but rather that the current tools of managing and evaluating information are ill-suited to the realities of the digital age. Some of the major instances of filter failure are inadequate information retrieval systems in clinical settings, and the problem of identifying all relevant evidence in a complex, diverse landscape of information resources.

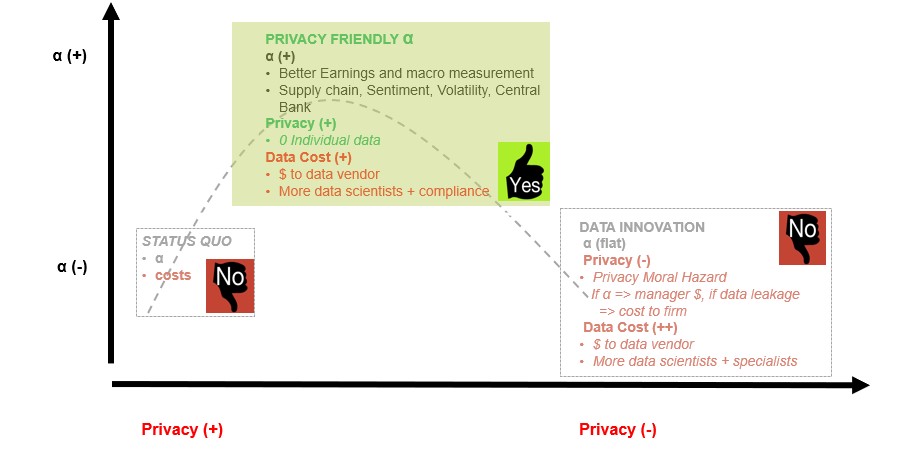

A way forward: Privacy-friendly α?

A year later, your PM, your quant, and the compliance officers sit down for another meeting. You all now agree that the picture may be more nuanced than you had assumed earlier and you try to design a better strategy. You find that some of the food data, when aggregated, was useful for predicting same-store sales. That was extremely useful for your firm’s PE arm that had invested in some food companies and couldn’t easily detect the trends. Your PM and head quant also believe that if they had aggregated information about consumption patterns — especially liquids — over various states, especially with the heat wave this year, it might have helped do better seasonal correction for macro data coming out this quarter as compared to official data from government agencies. So there are opportunities that are actually privacy-friendly or at least privacy-neutral: these strategies do not rely upon individual users losing control over their personally identifiable data and is more along the lines of what Ann Cavoukian writes about turning the privacy vs. security paradigm on its head and thinking of positive-sum messaging.

Some examples of privacy-friendly investment or social α may be:

- Better information on private firms’ broad consumption trends that is not available generally due to sparse analyst coverage.

- Better ESG and corporate governance being enforced by using anonymized and aggregated data from surveys and forums about employee happiness and their judgment of management effectiveness.

- Better macro-economic predictions that help foster improved monetary policy and more timely asset allocation, especially in difficult economic times or for poorer countries when these government data tend to be poorly measured.

- Using anonymous surveys or data from explicit public forums such as Twitter™ where users can provide feedback to the government about fiscal policy, or nudge corporations to act more ethically. The sentiment expressed in such surveys and tweets tends to be noisy but leading and hence can also be used for investing when appropriately combined with an aggregated credit card or other data or a prior strong view.

- A more detailed international supply chain of a company and comparing the CEO’s speech to her own previous speeches as well as to the speeches of all other CEOs in the sector using NLP to form a more informed view on whether the trade disputes with China will be enduring and lead to more global supply chain disruption.

Starting a conversation

Investment professionals are taking note. Bill Kelly, the CEO of Chartered Alternative Investment Analyst (CAIA) agrees with the potential alternative data offer: “Finding alpha in what have become highly efficient markets is increasingly a very difficult challenge. The advent of 1.2 million terabytes of alternative data represents a potential sea of inefficiency and the opportunity for alpha discovery.”

Yet the future privacy risks concern Bill; he believes that as an industry we are better off self-policing.

The client, regulator and legislature are mostly standing onshore observing and trying to understand what this all means. They will eventually weigh-in when hindsight is 20/20, and codification of regulation will take place via enforcement actions for decisions and actions taken today. The agency problem between the investment professional and the organization that signs her check is real. It must be self-policed with the utmost caution, erring on the side of the consumer who knowingly or unknowingly abdicated her rights to privacy. This is happening at a time when the definition of privacy has failed to keep pace with the rapid digitization of our world.

We are enthusiastic researchers ourselves and believe alternative data can truly change how we think about risk and reward in the context of the pressure to seek alpha in ethically appropriate ways. We have two broad suggestions:

1. A risk mitigation solution: Perhaps an answer to the data incentives is to form a committee in the firm similar to the IRB committee structure in healthcare that is a formalization of the meeting above, but one in which we reduce the moral hazard by making the CIO, to whom the PM reports, also wear the hat of the Chief Privacy Officer, and thus she would own the long-tail risk as well as the alpha. A long-tail risk manager, facing an ‘extinction-level event’ (ELE) after a data breach would, therefore, err on the side of demanding to see proof of alpha-creation well prior to the procurement of any sensitive data.

If compliance also had to report to the CIO, then compliance managers could move away from being “if, then” tick-box checkers to enterprise risk managers who care about long-tail protection for all people who contribute their data to ‘free services’ (search, social media) or ‘free-for-niche-purposes data’ (customer loyalty cards, gaming apps) but whose data could potentially be put at risk if a third-party data vendor leaks those data negligently or inadvertently.

2. A reward increasing solution: Examples of funds or companies that do not use individual data by design but are achieving investment alpha or improving outcomes for society — as suggested in the previous privacy-friendly α section — could also be powerfully effective in encouraging others to follow suit.

This is a complex topic but an important one. We do not have the complete answers but hope to hear from all the stakeholders and contribute to the conversation that is important to all of us — citizens, investors, vendors, quants, and PMs who want both privacy and alpha. Returning to healthcare, a sector that operates under high stakes and under urgency in search of finding cures for epidemics of life-threatening diseases from which all of humanity can benefit, it needs to live by the Hippocratic Oath: First, Do No Harm.

The overabundance of data is like laying back on a summer day and looking up at the clouds. The human tendency is to look up and see forms of animals and things — fanciful pictures. Connecting data to see something where there is nothing is the work of false wizards justifying their existence. Most times, clouds are just clouds. Making something out of nothing is a dangerous brew, especially when compounded by risking privacy for no apparent reason.